A Brief History of Andean Textiles

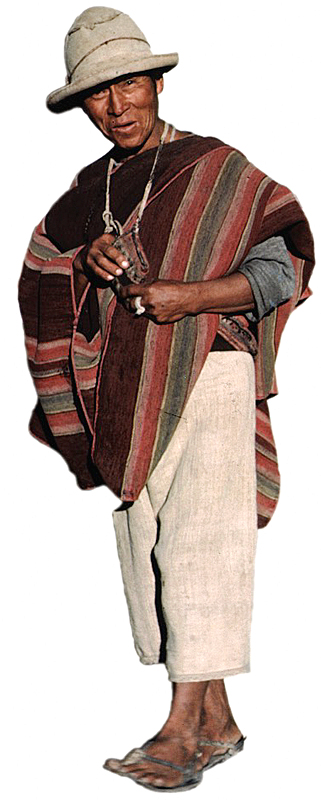

Altiplano men wore clothing made by women for millenia

Altiplano men wore clothing made by women for millenia

For over 5000 years Andean peoples have been creating content imbued costume textiles for the edification of the group and the exaltation of the elite. Beginning with the simplest of knotted techniques, these textile centric peoples eventually discovered all hand-made cloth manufacturing processes and also elaborated others unique to the region.

The concurrent development of refined animal husbandry ultimately provided superior raw material for creating textile displays supplanting the initial vegetal fiber based art. Simultaneously, fifty centuries of plant and mineral experimentation allowed for the discovery of a complex palette of dye shades with more than 200 colors eventually provided to the ancient weavers for artistic communication.

As early as 2500 BC and before, women twined and knotted stylized depictions of essential actors from their oral histories and myths into clothing and banners. Textile creation became the preferred method of visual aid for the communication of complex theological ideas and the display of the bearers concerns and allegiances. The ground breaking work of Dr. Junius Bird established that by the mid Third Millennium BC there was a voluminous textile production incorporating well designed, conventionalized images of the same fierce creatures of mythology that we see disseminated for thousands of years.

The harpy eagle, the condor, the serpent and the jaguar were all referenced in the canon of early textile artists as inhabitants of the physical realm with supernatural associations. This emphasis on the communicative nature of textile art was central to the mindset of the artists even before weaving was invented so that the primary focus of their sacred cloth, in all its intricate elaborations, was to convey a set of conceptual ideas and provoke emotions and reactions from the viewer. This traditional focus of Altiplano fiber arts aligns the female creators with the goal of artists worldwide: the embodiment of truth, beauty and communication in color and form.

Dr. Bird’s illuminating work at Huaca Prieta on the North Peruvian coast deciphering colorless fabric shreds uncovered the early development of this primal theme of Andean textile culture which persisted for thousands of years. This refinement of fabric communication continued into the twentieth century as witnessed in the artistic achievements of this volume. The elaboration of costume and display cloth into the banners of memory and distinction was in full blown execution even before the quantum leap to loom woven fabric. The women artists had taken the simple process of netting and transformed the products into wearable panels of articulation well before the development of loom technology. Therefore the expression of textile designs predate their ultimate refinements in execution; the innovations in weaving arose as part of the evolution of thousands of years of cruder, more laborious sacred art. Also note that besides textile creations for the dissemination of artistic renditions embodying culturally important figures, Dr. Bird found no comparative output in clay, stone, or any

Altiplano men wore clothing made by women for millenia other materials except for two imported carved lime gourds from the Ecuadorian culture of Valdivia, confirming the overwhelming importance of textile art in the Andes.

By the second millennium BC agriculture was well established and loom techniques began emerging utilizing such early methods as wrapped warp weaving and plain weaves made into painted cotton fabrics designed to carry political and metaphysical messages. Far more complex images were now possible with the new cloth production technologies. Into the middle of the First Millennium BC we have evidence of proselytizing cultures using textile creations to transport their beliefs in a diagrammatic form to distant audiences.

Meanwhile the recipient peoples already had their own multiform beliefs elaborated in cloth, first in knotted techniques, then embroideries, and finally weft tapestry and warp pickup structures as the evolution of textile art was independently advancing throughout Peru and Bolivia across the expanse of tribal groups.

All production avenues were being explored by the various Andean tribes in the explosion of textile innovations that marked the first millennium BC into the first centuries of the new era. By 2000 years ago the Andean peoples had collectively discovered all known textile techniques while inventing others unique to the region. This began an apex of textile excellence marked by such amazingly laborious expenditures as 10-20 woman years and more invested by the greatest artists of each generation on singular mantles and other costume textiles sometimes meant solely for internment with deceased ancestors to demonstrate devotion to their veneration. Incredibly fine and detailed cloths were woven and embroidered, knitted and knotted, to precise completion in stunning colors whose refined qualities are apparent today. Even though most cultures had at this time also developed sophisticated plastic arts and sculptures in ceramic, stone and metal, it was textile art that was the basis of picturing sacred concepts. This is evidenced by the nature of the designs employed in these non-fiber arts which all show subjugation to strictures only dictated by textile execution.

The Llama and the number 4 are ancient Andean cornerstones

The Llama and the number 4 are ancient Andean cornerstones

During the first Millennium AD tribal groups began to code information in fiber art through color and technical features which permitted accounting and mnemonic information to be transmitted along with the myths embodied in graphic images. This required that the audience, whether large or select, was privy to the meanings incorporated in their fabrics. In the case of the Nazca, knitted borders in colorful, non-sequential arrays and polychrome bean structures may have communicated information to the elite.

Concurrently the Moche people of Northern Peru are shown in many ceramic paintings analyzing decorated beans from which they were presumably reading messages in color and design. The two mysterious concepts share many features and perhaps signal the initial employment of color and form as communication strategies. Succeeding highland empires of the Wari and Inca innovate complex knotted cords called “quipus” to relay information in color and fiber variations to their cognoscenti, employing a decimal knotting overlay

The Llama and the number 4 are ancient Andean cornerstones which provides the mathematical component for this legible textile record. The select juxtaposition of colors would certainly have varied the intention of each by providing an intricate variety of combinations to relate ideas. Francois Sudre, in his 19th century visual code Solresol, showed that just the seven colors of the rainbow could convey language with all its nuance.

Concomitant with elaborate techniques came a greater desire for extreme achievements in the preparation of raw materials in fiber and color to realize the finest technical execution. Camelid based societies, like the Wari culture and the later Inca Empire, were necessary to foster the evolution of the best possible animal hair to use for spinning and weaving. Late in the first millennium AD, the Wari culture’s elite tunics utilize the most astonishingly tiny yarns, among the finest animal threads in world history, to produce singular cloth dense with a broad variety of crisply rendered graphic images.

Concurrently this highland based culture developed a canon of striped textile production both in weft tapestry and warp faced weaves. This aesthetic simplicity of finely dyed, juxtaposed stripes is the basis of most Altiplano textile art and it reaches its greatest expansion during the Colla Federation of Altiplano tribal groups in the 15-16th centuries based on these first millennium AD origins.

An Aymara woman weaving fabric

An Aymara woman weaving fabricusing a simple staked loom

By the start of the second millennium AD the use of animal hair yarns for textile creation was ubiquitous whether the culture and its feminine artists were coastal or mountain based. The adoption of camelid fiber to create elite garments and ritual furnishings became complete by this period due to its superior color range, luster and durability compared to vegetal fibers such as cotton.

Trade networks were extensive and access to a wide choice of materials for textile manufacture was the rule for most federations and kingdoms with the differences in artwork often based on local dye options and traditional regional preferences rather than overall raw material availability. Most elite fabric throughout the Andes during this period was being made with tapestry weaving for pageant, ritual and ceremony. The tribal groups on the Altiplano diverged from the norm of weft based textiles, preferring to enlarge on the employment of simple warp striping and color field beauty to convey origin, distinction and belief.

During the period from 1000-1500 AD on the Altiplano, a broad array of tribal groups were drawing significance to themselves through codified color and stripe placement on their warp faced fabrics. The female artists challenge was to distinguish herself by excelling in the execution of her fiber skills while weaving the appropriate ceremonial clothing for herself and her family. Centuries of refinement in camelid husbandry resulted in ever better primary material for the spinning process upon which all cloth creation is based. Millennia of plant and mineral study had led to ever wider choices in dye hues though often potential diversity in color was sacrificed to the desire to follow ancestral models. The Inca Empire swept over the Altiplano and enveloped the Colla Federation in its hegemony but never completely changed the various tribal textile expressions from their ancient ways. Each continued to evolve in textile quality and style along the lines of their particular artistic and functional needs.

The European conquest of South America removed the Incan overlords from their supervision of the Aymara and replaced them with a hacienda system of independent colonists superimposed on the ancient system of community organization based in families, allyu’s and tribes. The subjugated peoples continued to elaborate and improve on their textile arts throughout the Colonial Period as they maintained ceremony and ritual outside of European awareness. This culminated in the indigenous revolutionaries rising up in revolt against their overlords late in the 18th century behind the wearable textile banners of their leaders.

As a last desperate measure of a dying empire, the Spanish crown outlawed ceremonial textiles in 1780 but it was too late; the breach was already permanent. After independence, in the new freedom of the Republican period during the 19th century, there was a florescence of warp faced textile art for the renewed indigenous pageants and festivals. Most of the textiles in this collection were made during this renaissance in Altiplano costume art as the women artists drew upon centuries, even millennia, of progressions in practical knowledge and physical skills in order to execute these sublime masterpieces of feminine fiber art.